Best viewed in Chrome, desktop. On smartphones, use the right side for panning, and the left side for tapping on sentences/names.

CONCEPT, RESEARCH, UI&UX DESIGN, DEVELOPMENT

Deniz Cem Önduygu

UI&UX DESIGN, DEVELOPMENT (2015–19)

Hüseyin Kuşçu

PROGRAMMING FOR STATIC VERSION (2014)

Eser Aygün

FEATURED ON

Here’s a surprisingly useful thinking tool for anybody interested in the history of Western philosophy: a sort of garden of forking paths of argument. https://t.co/AH1ophVXH8

— Daniel Dennett (@danieldennett) October 9, 2018

A stunning, interactive visualization of the history of philosophy by @denizcemonduygu, showing the positive and negative connections between some of the key ideas and arguments from philosophers https://t.co/vHvluivXsM

— Oxford Philosophy (@OUPPhilosophy) October 9, 2018

Love this interactive timeline of philosophical ideas. Not only to you get the ideas, but linkages showing who agreed/disagreed with whom.https://t.co/y2H0j2LmbA

— Sean Carroll (@seanmcarroll) October 9, 2018

This is my ever-growing summary of the history of Western philosophy showing the positive/negative connections between some of the key ideas/arguments/statements of the philosophers. It is not an automated text analysis project; the work of summarizing (primary/secondary) literature and drawing connections is done by me, so it’s a never-ending work-in-progress. It started with Bryan Magee’s The Story of Philosophy and Thomas Baldwin’s Contemporary Philosophy as the main references, and it has been expanding with hundreds of others. (The reference is noted with the book icon that appears when you hover/click on a sentence. And yes, I’ll hopefully start adding philosophers from other traditions after some more work on the Western story.)

First off, let me announce that though I have been actively working on this project since 2014 and have a good grasp of the fields and the philosophers I’m interested in; I’m not an academic historian of philosophy. This is a personal project that I’m doing in my own time, with my auto-didactic knowledge, for myself; and I’m sharing it to get feedback and to make it accessible to those who are interested in philosophy and/or visualization. As much as I find this way of looking at philosophy productive (and fun) for many reasons, I’m not proposing that this is the right way to look at it; it is just one version that I like to see and use – an organized and dynamic collection of notes, letting me see how these ideas have developed, from a distance.

I believe I’m not alone when I say that I understand an idea, argument, position, or concept better when I see it along with others that are similar to it and in contrast with it. Accordingly, I like to think that this is not just a historical project, useful for people specifically interested in the history of the field; what is also valuable here is the ability to see, by clicking on a sentence and displaying its connections, what different things can be said on a subject (how many perspectives there can be, which are hard to be all dreamed up by a single person) independently of who said them and when – independently of a direct interest in the history of philosophy. In this respect, it can function as a thinking tool that helps people, as it helps me, think through these ideas by showing different formulations and negations of them. It can also serve as a preliminary academic tool that provides entry points to the literature by listing some of the relevant names and texts. (Philosopher-based engagement in philosophy, though criticized by some, is an efficient method for many people – I think this project is neutral in that regard: you can choose to explore it as idea-based or philosopher-based. I find both of them useful, and mostly employ a combination of them.)

Another reason “History of Philosophy” could (increasingly) be a misnomer for this project is that I keep including figures from contemporary philosophy and connecting them to the past as well as to each other. Seeing history of philosophy continuous with its current state, this was my intention all along, hoping that it will be able to give structured overviews of the more recent debates along with their historical backgrounds. As Baldwin reminds,

“[C]ontemporary philosophy is dialectical in its method: new arguments necessarily make reference back to earlier positions which provide the background for understanding the commitments which the arguments seek to challenge. (…) The relation of present arguments to past debate provides by itself good enough reasons for regarding the continuation of such debates as the only way of improving our understanding.”

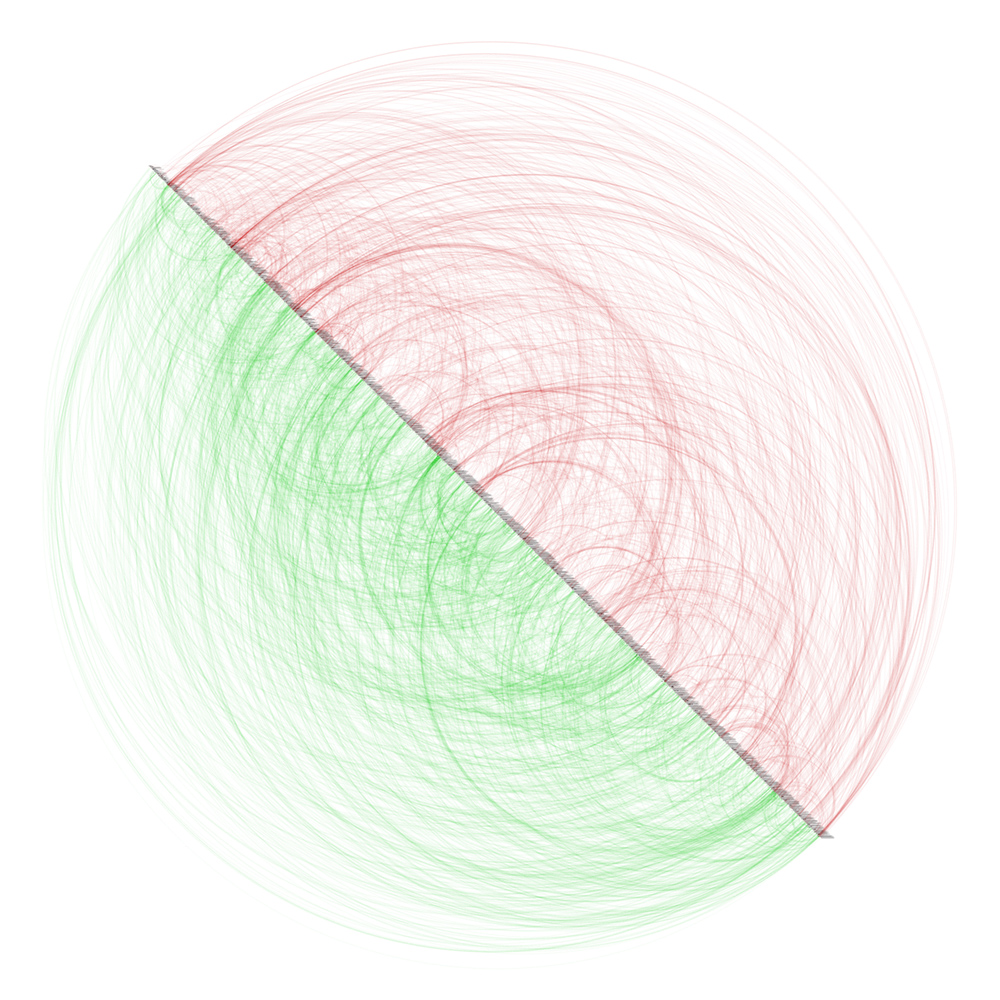

What exactly am I doing? When I’m reading a text, I’m summarizing it with isolated sentences. In the next step, I’m optimizing them so as to include all of the ideas with the minimum number of efficient sentences, in a meaningful order – this is the hardest part. (This means I usually don’t include every step of a long argument but settle for a condensed form of it or only its conclusion(s). I usually shorten/paraphrase a sentence if it’s from secondary literature, but I try to quote it as it is – as long as it’s not too long – if it’s from the philosopher.) For each sentence, I’m recording the reference, specifying the filter categories for branches (metaphysics, epistemology, etc.), and the tags (names of arguments, theories, -isms, etc.) which will be displayed on its left. Then I’m noting down the positive/negative relations to other statements, putting all this information in a spreadsheet in a machine-readable format, going through everything to look for further possible connections, feeding it to the visualization I’ve designed, and finally using the visualization to check for further possible connections to be added. If there is an agreement or similarity between two statements, they’re connected with a green line. If there is disagreement or contrast between the statements, they’re connected with a red line. Some of these connections are acknowledged by the philosophers or the historians, some of them are drawn by me.

Maybe you can complain that I have low standards for the connections. The question frequently arises: “Clearly these two sentences are talking about the same thing, but did they read that person from the 18th century, or did they come up with it by themself?” Except for a few specific cases, I ignored this question for two reasons. First, most philosophers read most people before themselves and they don’t always add extensive lists of names or references for every argument they produce; so I usually assume there may be an influence even when it’s not acknowledged. Secondly, and more importantly, the fact that there may not be a direct influence (acknowledged or not) doesn’t violate my concept of connection here: The lines for me do not always depict a direct transfer between two people; I think of them as mapping the development and the diversification of ideas throughout time, connecting different perspectives on a subject. This choice is also evident in the non-directionality of the connection lines: the direction of a possible direct transfer is obvious when there are dozens of years between two philosophers, but for those who live and write during the same years, it is quite possible that they take ideas from each other, get in conversations, or influence each other in various ways.

I am of course aware that not everybody is here and the ideas-connections of the included philosophers aren’t exhaustive. I am also aware that the level of detail isn’t the same for every philosopher. The content for some philosophers are more beginner-level because they come from texts intended for general audiences, and some philosophers have more detailed and extensive content because I had the opportunity to concentrate on them by reading multiple documents, including their own output. My idealistic goal is to slowly go through everybody so as to keep a somewhat homogeneous depth overall – this is a continuous effort which will proceed in parallel with the work of adding new names. I don’t think this project can ever be “completed”, but I will be expanding it by adding information from everything I read – probably until I die – in the hope of making it as rich as I can. And yes, I may be prioritizing philosophers and subjects I like in the process. I’ll also be adding more thinkers who aren’t strictly philosophers but had considerable effect on philosophy (like Darwin, Freud, Gödel, etc.) and philosophers from other traditions. So don’t get mad if your favorite philosophers or ideas aren’t here: this is not a finished product, and they probably are in my to-add list. (I’m open to corrections and suggestions.) You can see the list of updates on the Updates page where you can also subscribe to get notification emails when I add new content or make interface upgrades.

One warning: Browsing this visual summary cannot substitute reading a good book of history of philosophy, let alone studying the original texts by the philosophers. These sentences are dry summaries of long, intricate argumentations and some of them are not even comprehensible if you’re not already familiar with the subject/philosopher. Some of these ideas are best understood within the historical/political context, as they are presented in books of history of philosophy. So no, you shouldn’t expect to learn philosophy or the history of it by just using this summary. As I wrote in the beginning, this is mainly an organized collection of notes to myself and I believe it can function as a thinking/research tool for other people as well. (I also believe it can function as a teaser for people who aren’t familiar with the field, making them feel curious about an idea or discussion and start reading about that.)

—

I conceived and sketched this project in February 2012 while organizing my notes from my readings (“There should be a global and systematic way to see all these relations! How about…”) and started working on it in February 2014.

I am deeply thankful to Hüseyin Kuşçu who offered his programming skills for the creation of the interactive version on the Browse page.

I also thank my friend Eser Aygün for writing the program that automatized to a great degree the transition between the spreadsheet that I fill in and the visualization I’ve designed, for the static version in the beginning of this project. It was the catalyzer that kept me motivated by showing the visual results every step of the way.

And here are the names of nice people who offered content corrections or improvements that I was able to apply so far: Sedat Hasoğlu, Jakub Rudnicki, Matheus Schneider, César Tomé López, Sylvia Wenmackers, Miguel Mateo La Salle, Juan Antonio Ricci, Simo Raittila, Stephen Laudig.